The A-Z of UX: M is for Mental Models: 8 principles for designing products that match how users think, and expect

- UXcentric

- 2 days ago

- 13 min read

Darren Wilson

After previously exploring ‘Layout’, which shapes what users see, it’s time to look beneath the surface at what shapes how users expect things to work.

That underlying expectation is a user’s ‘mental model’.

A mental model is the internal explanation a person has about how a system works. The model is constructed from our past experiences, familiar patterns, cultural norms, and repeated interactions with similar products.

Users rely on these models to predict outcomes, make decisions, and recover from mistakes.

When a product aligns with a user’s mental model, it feels intuitive. People move quickly, confidently, and often without conscious thought.

When it doesn’t, even a visually polished interface can feel confusing, fragile, or slow.

Importantly, mental models are not taught by documentation or onboarding.

They are assumed. Users arrive with expectations already formed, and your design either reinforces them or fights them.

Understanding mental models helps explain why:

Users ignore options that appear obvious to the team that built the product

Navigation can look tidy yet still feel disorienting

Features are blamed when the real problem is that expectations are not met

People say, “This doesn’t work how I thought it would”

I see these kinds of issues regularly when conducting user research on existing products and experiences, and during user acceptance testing for new ones.

Mental models are not static. They evolve as technology changes, and they differ across user groups, generations, and domains.

So the goal isn’t one ‘correct’ model. It should be designed to meet your audience's dominant expectations and handle mismatches gracefully.

A well-designed product recognises this and works with those expectations, not against them.

"People’s conceptual models of how things work are formed largely by experience."

Donald Norman,

The image above illustrates how expectations are formed through experience, tested through interaction, and reinforced or reshaped over time.

“Users don’t care how the software works. They care about getting their work done.”

Alan Cooper et al.

Principle One: Match the user’s mental model, not the system’s

Users do not experience your internal architecture, technical constraints, or organisational structure. They experience outcomes.

When a product reflects how the system works rather than how users think, friction appears almost immediately. This is one of the most common and costly mental model mismatches in digital products.

Teams often structure interfaces around backend services, department ownership, or technical domains. From the user’s perspective, none of this matters.

This is also where teams tend to overestimate how much users will ‘figure things out’ on their own.

Equally, I’ve also seen users blame themselves for it, and once they have seen how it should work, you will often hear that they would have worked it out in time.

Where products go wrong

Navigation mirrors an org chart

Labels use internal terminology instead of user language

Settings are grouped by implementation rather than intent

Users must understand the system before they can use it

In these cases, users are forced to learn the product’s model instead of relying on their own.

“When users’ mental models differ from the design model, confusion is inevitable.”

Nielsen Norman Group, Megan Chan

What to look for

Can users predict what will happen next?

Are labels describing user intent or system function?

Would someone unfamiliar with the system explain this the same way as the team would?

Real-World Examples

Online shopping relies on a simple mental model: users choose what goes into their basket, and nothing appears there without intent.

✅ Good example – Amazon Basket Control

Users deliberately add items to their basket and review them before checkout. The system mirrors real-world shopping expectations: control sits with the customer.

❌ Bad example – Pre-Selected Add-Ons (e.g. airline insurance)

Some airlines pre-select insurance or extras during checkout. Items appear without explicit user intent, violating the “I choose what goes in my basket” mental model. This is especially bad if the add-ons are not visually obvious and clear how to remove them.

Principle Two: Familiar patterns reduce cognitive effort

Users rely heavily on recognition rather than reasoning.

When an interface uses patterns they already understand, people can focus on their goal instead of working out how the system behaves.

Mental models are built through repeated exposure.

Users develop expectations about how common elements behave, such as where navigation lives, how filters work, what happens when a button is pressed, or how a list can be sorted.

This is why familiarity often outperforms novelty.

Design teams sometimes introduce new patterns to differentiate or modernise an experience.

But unless there is a clear benefit, novelty forces users to form a new mental model from scratch, increasing effort, hesitation, and error.

“Users spend most of their time on other sites. This means that users prefer your site to work the same way as all the other sites they already know.”

Jakob Nielsen

Where products go wrong

Common controls behave differently without explanation

Established conventions are replaced for aesthetic reasons

Interactions are “clever” but not predictable

Familiar gestures or patterns are partially implemented

What to look for

Is this pattern already widely understood?

Are we changing it for real usability benefit or novelty?

Would a first-time user recognise how this works?

Real-World Examples

Familiar interface patterns allow users to rely on recognition instead of having to decode how something works.

✅ Good example – Facebook Bottom Navigation

Home, Reels, Friends, Groups, Notifications, Profile. The layout matches established mobile conventions. Users recognise it instantly. The app uses text and icons to help as well.

❌ Bad example – Early Snapchat Gesture-Only Navigation

Early versions relied on hidden swipes with minimal visual cues. New users struggled because the navigation model was invisible. Having it as an option, or telling people what the new behaviour was, would have been much more sensible.

Principle Three: Language and labels shape expectations

Words do more than describe actions. They set expectations about what will happen next.

Before clicking, tapping, or submitting, users make a prediction: Where will this take me? What state will I be in afterwards? That prediction is their mental model in action.

When labels are clear and specific, expectations are met. When labels are vague, abstract, or marketing-led, users are forced to guess.

I’ve seen this in product testing where everything is technically usable, but users still say they lack confidence and trust because the language leads them to expect something different.

"Every question mark adds to our cognitive workload, distracting our attention from the task at hand."

Donald Norman

Where products go wrong

Ambiguous CTAs (“Continue”, “Manage”, “Advanced”)

Labels that hide consequences

Internal or technical language leaking into UI

Similar actions are described inconsistently

What to look for

Could you predict the outcome solely from the labels?

Do labels reflect user intent or system mechanics?

Are similar actions described consistently?

Real-World Examples

Labels set expectations before an action is taken. When wording is clear, users move confidently. When it’s vague, hesitation follows.

✅ Good example – “Add to Basket/Bag” in E-commerce

Clear action. Clear outcome. Users know exactly what will happen next.

❌ Bad example – Ambiguous “Continue” buttons

“Continue” might mean save, submit, confirm, or progress. Without clarity, users hesitate because the consequences are unclear.

Principle Four: Flows should mirror real-world processes

Users don’t just carry expectations about individual screens or controls. They also carry expectations about sequence, i.e. the order in which things should happen.

Mental models are heavily influenced by how tasks work in the real world.

When a digital flow mirrors that natural order, users move through it with confidence.

When it doesn’t, they hesitate, backtrack, or lose trust in the system.

For example, people generally expect to:

Review information

Make a decision

Confirm an action

See a clear outcome

In an online checkout experience, users expect to review the basket before choosing delivery and payment, not the other way round.

When a product forces users to commit before they feel ready, or jumps them out of sequence, it breaks their mental model of the task.

“People expect systems to behave in ways that are consistent with their understanding of the world.”

Donald Norman

Where products go wrong

Steps are ordered for system convenience rather than user logic

Users must provide information before understanding why it’s needed

Confirmation happens too late, too early, or not at all

Users are forced to mentally reconstruct the process as they go

These issues often show up in forms, checkout flows, configuration tools, and enterprise systems.

What to look for

Does this flow match how someone would describe the task out loud?

Has the user ever asked to act without enough context?

Would removing a step make the process feel more natural?

When flows align with real-world expectations, users rarely notice them.

When they don’t, even small friction feels amplified.

And if a system behaves correctly, but the flow feels wrong, has it really succeeded?

Real-World Examples

Users expect digital tasks to follow the same logical order as their real-world equivalents. When the sequence feels unnatural, confidence drops.

✅ Good example – Booking.com Booking Flow

Your selection: Select property & dates → choose room preference → reserve

Your details: Prefilled details → Add any extras and special requests

Finish booking: Confirm → pay.

The order matches how people naturally book accommodation.

❌ Bad example – Forced Account Creation Before Seeing Price

Some travel or SaaS sites require registration before revealing pricing. This forces commitment before evaluation, disrupting the expected order of review → decide → confirm.

Principle Five: Users expect things to live in predictable places

Mental models help users answer a simple but critical question: “Where would I expect to find this?”

Initially, if users can’t answer that quickly, cognitive effort increases even if the feature itself works perfectly.

Over time, users may develop strong expectations about where features, controls, and information are located within a product.

Navigation structures, settings locations, and repeated patterns all reinforce these expectations.

When a product respects this predictability, users move quickly. When it doesn’t, users hunt.

"Consistency and standards: Users should not have to wonder whether different words, situations, or actions mean the same thing."

Nielsen Norman Group

Where products go wrong

Features are grouped by internal ownership instead of user intent

Similar functions live in different places across the product

Settings are scattered or duplicated without clear logic

Navigation labels overlap or feel interchangeable

The result isn’t always an immediate failure. It can be a slow erosion of confidence. Users feel the product is harder to use than it should be, even if they can technically complete tasks.

What to look for

Would most users look here first?

Is this location consistent with similar features elsewhere?

Are we prioritising clarity over completeness?

Good structure supports mental models silently. Poor structure forces users to constantly re-orient themselves.

Real-World Examples

People build strong expectations about where features and controls should live. When placement aligns with those expectations, navigation feels effortless.

✅ Good example – Profile Avatar for Settings

Clicking your avatar reveals account settings across platforms. This pattern is now universal.

❌ Bad example – Settings Hidden Under Random Icons

Some apps bury settings under unrelated icons or deep menus, forcing users to hunt for them.

Principle Six: Feedback confirms or breaks the user’s mental model

Users are constantly testing their understanding of a product.

Every action they take (clicking a button, submitting a form, changing a setting) is followed by an implicit question: Did that do what I expected?

Feedback is how the system answers that question. When feedback is timely, clear, and proportional, it reinforces the user’s mental model. When it is delayed, unclear, or missing entirely, trust erodes quickly.

Good feedback doesn’t just confirm success. It helps users understand:

What has happened

What state is the system now in

What they can do next

“The system should always keep users informed about what is going on, through appropriate feedback within reasonable time.”

Nielsen Norman Group

Where products go wrong

Actions produce no visible response

Feedback appears far away from the action that triggered it

Errors are shown without guidance on how to recover

Success states are ambiguous or easy to miss

In these situations, users are left guessing. They repeat actions, abandon tasks, or assume the product is unreliable, even when it’s technically working fine.

What to look for

After every meaningful action, is the outcome clear?

Does feedback appear where the user’s attention already is?

Does error feedback explain how to fix the problem, not just what went wrong?

Good feedback reassures users that their understanding of the system is correct. Poor feedback forces them to rebuild their mental model through trial and error.

Real-World Examples

Every action tests a user’s understanding of the system. Clear feedback reinforces that understanding; silence forces them to guess.

✅ Good example – Google Docs “Saved to Drive” Indicator

Continuous feedback on saving reassures users that their work is secure.

❌ Bad example – Form Submission with No Confirmation

A page reloads silently after submission. Users resubmit because they assume failure.

Principle Seven: Change breaks learned mental models, so handle with care

Mental models are not just formed; they are learned and reinforced through repetition.

As users become familiar with a product, they stop consciously thinking about how it works and focus on what they want to achieve.

This efficiency is fragile. Even small changes can make experienced users feel suddenly incompetent, not because the product is worse, but because the behaviour they relied on no longer works as expected.

The resistance I see isn’t about users disliking change. It’s about losing behaviours they’ve invested time learning, especially when the new experience isn’t intuitive or compelling enough to justify the shift.

If you break a mental model, you’re asking users to relearn. Relearning has a cost. That cost must be justified by perceived value that Is great than the risk.

“People feel frustrated when things they know how to do suddenly no longer work.”

Donald Norman

Where products go wrong

Features are relocated without explanation

Familiar workflows are redesigned “for consistency”

Terminology changes without considering existing users

Updates prioritise new users at the expense of experienced ones

While change is often well-intentioned, it can unintentionally invalidate what users have already learned.

What to look for

Are we respecting existing user habits?

Have we made this change discoverable and explainable?

Is there a transition path for experienced users?

Good products treat learned behaviour as something to be protected, not casually overwritten.

Real-World Examples

Once users learn how something works, that behaviour becomes automatic. Sudden changes disrupt that efficiency and can feel like a regression.

✅ Good – Incremental change that preserves core patterns

Adobe introduces updates incrementally. Layout and functionality changes are rolled out gradually, preserving familiar patterns. Users are guided through what’s new and can adapt at their own pace, minimising disruption while enabling continuous improvement.

❌ Bad – Microsoft Office Ribbon (2007 Launch)

The shift from menus to Ribbon disrupted long-established workflows. Power users initially felt lost.

The Excel 2007 Ribbon flattened out to show all the commands in the standard tabs (Image Credit - Martin Colebourne)

Principle 8: Mental models evolve, so products must adapt

Mental models are shaped by experience, and experience changes over time.

As technology, interaction patterns, and dominant platforms evolve, so do users’ expectations of how products should behave. What once felt intuitive can quickly feel outdated, while new behaviours become second nature surprisingly fast.

This means mental models are not something designers can “solve” once and move on from. They require ongoing attention.

Users who have spent years interacting with desktop software, command-line tools, or form-heavy systems often expect explicit actions, visible structure, and clear confirmation. Users shaped by mobile-first, feed-based, or gesture-driven environments may expect immediacy, continuity, and implicit state changes.

Neither mental model is wrong. Problems arise when products are designed as if only one of them exists.

Mental models don’t just differ between people. They shift over time, shaped by technology, culture, and repeated exposure to new interaction patterns. This is why patterns that feel intuitive to one group can feel unnecessary or confusing to another.

“People’s conceptual models of how things work are formed largely by experience.”

Donald Norman

Where products go wrong

Products cling to legacy interaction patterns despite changing expectations

Newer patterns are adopted without considering existing users’ mental models

Updates assume users will automatically adapt to new behaviours

Teams design for “how it used to work” or “how it should work” rather than how users now expect it to work

In these cases, users often experience friction that’s hard to articulate. The product doesn’t feel broken, but it feels off.

What to look for

Which mental models are we currently designing for?

Are we balancing existing expectations with emerging ones?

Would this interaction feel intuitive to someone encountering it for the first time today?

Products that age well evolve their design models alongside their users’ mental models, without forcing abrupt or unexplained shifts.

This often shows up across generations, but it’s really about exposure, not age. Some Gen Z users live in enterprise tools all day; some older users are mobile-first. Segment by behaviour and context, then test assumptions.

Real-World Examples

As dominant interaction patterns shift, so do user expectations. Products that fail to evolve alongside those expectations begin to feel outdated.

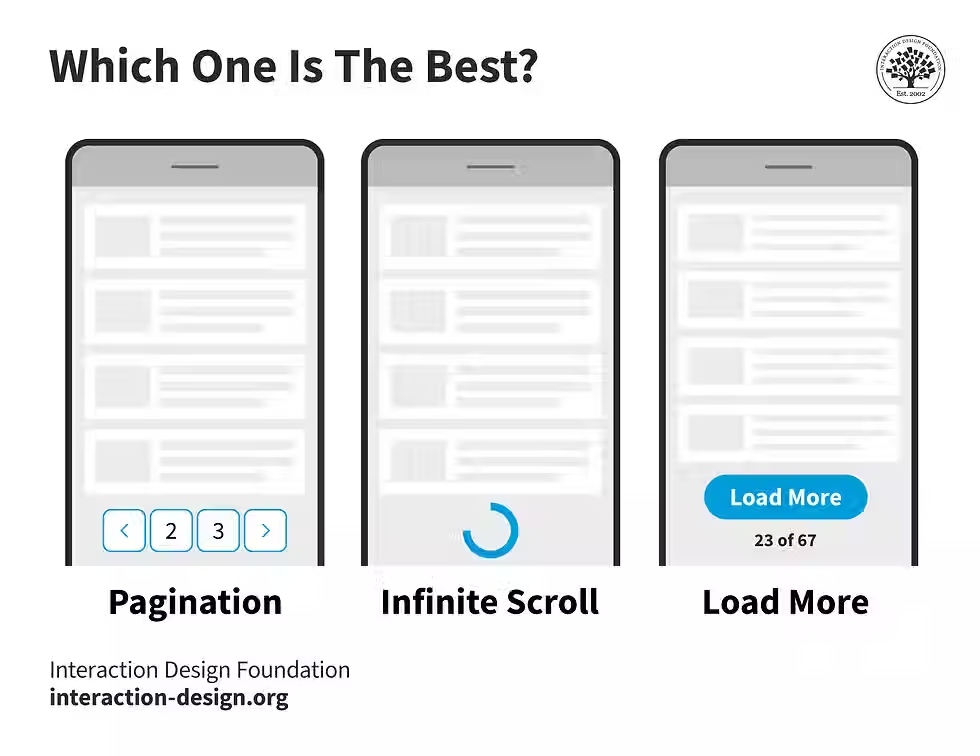

✅ Good – TikTok Vertical Infinite Scroll

What once felt novel is now dominant. Users expect vertical swipe to mean continuous discovery.

❌ Bad – Desktop-Style Pagination on Mobile

Some mobile sites still use small page numbers rather than infinite scroll, which clashes with modern mobile expectations.

Final Thoughts

Mental models determine whether a product feels intuitive or frustrating, whether users move with confidence or hesitation, and whether problems are blamed on the system or on themselves.

Most usability issues I encounter aren’t caused by poor execution, but by mismatches between what a system does and what users expect it to do.

Good design doesn’t ask users to adapt to the system’s logic. It adapts the system to the logic that users already carry.

This doesn’t mean freezing designs in time or avoiding change. Mental models evolve, and products must evolve with them. But change needs to be intentional, explainable, and respectful of what users have already learned.

If there’s one takeaway from these principles, it’s this:

Don’t ask users to learn how your product works.

Design your product to work the way users already expect.

AI is accelerating mental model change

AI-driven systems are accelerating this shift. As products move from deterministic behaviour (“do X, get Y”) towards probabilistic outcomes, users form different expectations about control, predictability, and explanation.

In these systems, users no longer expect to fully understand how something works internally. Instead, their mental model becomes: the system infers, adapts, and may occasionally be wrong.

This makes feedback, transparency, and recovery even more critical. When AI systems fail silently or behave unexpectedly without explanation, trust collapses far faster than in traditional interfaces.

What this means for you

Mental model issues rarely show up as obvious usability bugs. They surface as confusion, hesitation, rework, or a general sense that a product is “harder to use than it should be.”

In practice, this means:

Refactors and consistency clean-ups often break learned behaviour, even when functionality improves

“Confusing” feedback usually signals an expectation mismatch, not a user failure

Architectural clarity should never take precedence over behavioural predictability

Protecting existing mental models is a product decision, not just a design one

Practical next steps

Audit your product for assumption mismatches

Test labels, flows, and feedback against user expectations

Treat learned behaviour as something to protect, not overwrite

Revisit mental models regularly as your audience and context evolve

When users say “this isn’t how I expected it to work”, that’s often one of the most valuable pieces of feedback a product team can receive.

Further Reading (recommended)

Donald Norman — The Design of Everyday Things

Nielsen Norman Group — Mental Models & User Expectations

Alan Cooper — About Face

Steve Krug — Don’t Make Me Think

Luke Wroblewski — Mobile First

Get in touch with the author

Darren Wilson

Managing Director at UXcentric

07854 781 908